Get to Know your Parkinson’s – Part 1

Reading about Parkinson’s can be discouraging because, unfortunately, whatever type you may have, your condition will likely progress and get worse over time. However, knowledge is power, and knowing what to expect down the line will help you prepare and take action to maximize your chances of maintaining good quality of life. No matter what stage your Parkinson's is at, it is normal to feel fearful of the future, and while no-one can give you a definite prediction of your specific rate of disease progression, taking control can help relieve much of that fear. Knowing that you are prepared for whatever may happen will help you find peace and calm and allow you to enjoy each day to the fullest.

In this article series we will cover several aspects of Parkinson’s disease which are a source of concern, anxiety, or misunderstanding for patients and their families. This article will explain the diagnosis process, why it usually takes so long, and what challenges doctors and patients face regarding diagnosis. We will also discuss the use of subtypes and staging that are common in describing the progression of Parkinson’s disease.

Diagnosis can be complicated

Receiving a diagnosis of Parkinson’s is often accompanied by many emotions. People frequently want to know how definite the diagnosis is. Might there have been a mistake? Might it be something else? Strictly speaking, the diagnosis is never definite, since a definite diagnosis requires examination of a brain sample under a microscope. Obviously, this isn’t practical. Instead, neurologists make their diagnosis based on clinical findings, and describe it as being either clinically established or clinically probable. To complicate things further, at the early stages diagnosis is even harder because the symptoms are not specific to Parkinson’s. Early symptoms are mostly non-motor (meaning that ability to move remains unimpaired) and non-specific, and may include sleep disturbances, constipation, and loss of smell.

So how does a neurologist decide that you might have Parkinson’s?

Often the recognition that one has Parkinson's occurs when tremors appear. But this method of recognition is flawed, as some people with Parkinson’s may not experience tremors at diagnosis, and may never develop any tremors. The sine qua non of Parkinson’s is actually “bradykinesia”, which means slow movement. This may be a general slowness accompanying any movement, such as slower walking, slowness of one arm, walking with a limp, etc. The diagnosing doctor will most likely also check for rigidity or muscle stiffness when examining you, which you may even feel yourself.

Every person has their own unique Parkinson’s disease

Parkinson’s is one of the most complex conditions out there; you may have heard the saying that no two people have the same condition. In a recent article in the leading medical journal The Lancet [1], Bastiaan Bloem, Michael Okun, and Christine Klein argue that “every person has their own unique Parkinson’s disease”. They support this claim with three important observations: (1) there are many causes for Parkinson’s which may differ between individuals; (2) even for people with the same underlying cause, the symptoms, their rate of progression, and the degree of disability which they cause vary greatly; and (3) for each individual, the same symptom with the same severity will have a very different impact on their wellbeing and functioning.

Nonetheless, it is still common practice to talk about Parkinson’s subtypes and stages. The term “subtypes” refers to different ways that Parkinson’s can present through symptoms, for example tremor-dominant versus other types without significant tremor or any tremor at all. Stages refer to the progression of the disease over time, with the number of symptoms increasing and their severity worsening.

1. Stages of PD

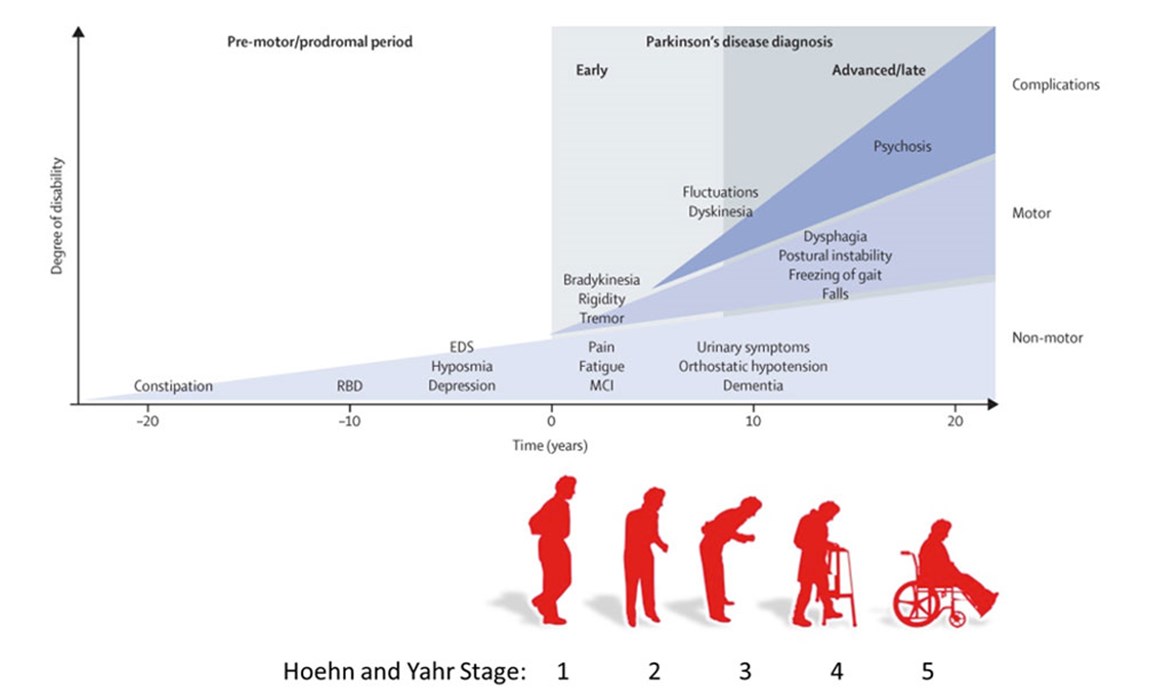

Officially, the staging of Parkinson’s still follows the Hoehn and Yahr staging, whereby the symptoms initially start on one side of the body only. This is Stage 1.

Then symptoms progress to involve both sides of the body. This is stage 2.

At Stage 3 there is mild to moderate bilateral disease with some postural instability, yet the patient remains physically independent, at Stage 4 there is severe disability but the patient is still able to walk or stand unassisted, and at Stage 5 the patient is wheelchair-bound or bedridden unless aided.

A limitation of this staging classification is that non-motor symptoms, such as cognitive decline and hallucinations, are not taken into consideration when determining the stage of the disease. Typically, these symptoms become the most troublesome at the later stages (Stages 4 and 5).

Sources of figures:

- Kalia LV, Lang AE. Parkinson's disease. Lancet. 2015 Aug 29;386(9996):896-912. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61393-3. Epub 2015 Apr 19. PMID: 25904081. (Top figure)

- Iheagwam, Franklyn Nonso, and Sifon Ita Etefia. "Recent Advances on the Management of Parkinson’s Disease: A Review." International Research Journal of Medical Sciences (2019). (Bottom figure)

At the earlier end of the spectrum, prior even to Stage 1, there often are symptoms that precede the diagnosis, such as constipation, sleep disturbance, loss of sense of smell and low mood (see top figure).

2. What type of Parkinson’s do I have?

As we mentioned above, Parkinson’s has a very broad spectrum of symptoms and, consequently, every person has a different experience in terms of the first symptoms that are noticed, how fast the condition deteriorates, which symptoms become the most bothersome, how these problems impact their lives, how they respond to medications, their medication choices and preferences, device-aided therapies and lifestyle changes.

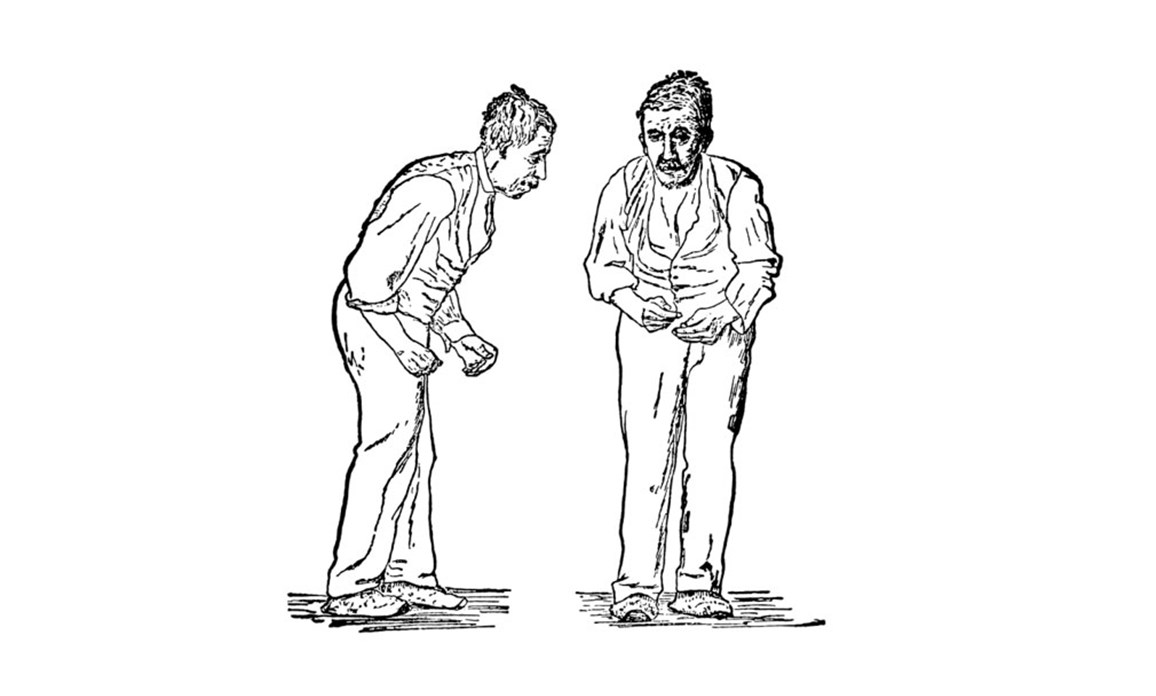

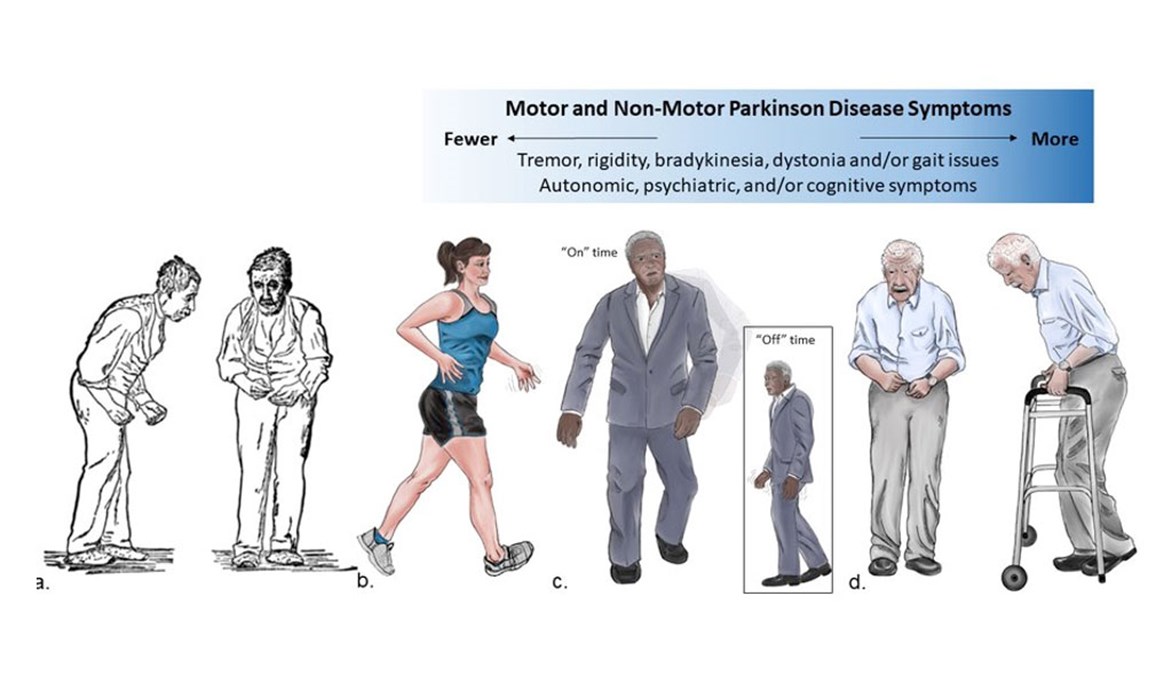

A recent paper by Armstrong and Okun [2] challenges the classic stereotype of an old man hunched over with his tremulous arm bent at the elbow.

The old classical textbook image:

SOURCE: Front and side views of a man portrayed to be suffering from Parkinson's disease. These are woodcut reproductions (of two collotypes from Paul de Saint-Leger's 1879 doctoral thesis, Paralysie agitante..etc.) published in Gowers, William Richard (1886). "Fig 145 — Paralysis agitans. (After St. Leger.)". A Manual of Diseases of the Nervous System. II. London, United Kingdom: J. & A. Churchill. p. 591. Retrieved 2011-03-24.

The new image:

Although this is indeed a typical patient, with similar images appearing in many medical textbooks and professional articles, there are so many other types of people who can have Parkinson’s with quite different symptoms. Because this diversity has not been emphasized enough over the years, anyone not fitting this “classical” picture is likely to have an even longer delay in diagnosis and also perhaps suffer more from stigma. For example, an active and fit mom with young-onset PD may feel even more uncomfortable to share her diagnosis, or even seek help, because of the perception of it being “an old person’s disease”.

There have been several attempts to characterize different subtypes of Parkinson’s.

One method is to determine whether there are any tremors, and the person's age at the time of first symptoms onset. An example is the following classification by Selikhova and colleagues [3].

- Earlier disease onset (EDO): Below age of 55 years at disease onset.

- Tremor dominant (TD): Aged 55 years and over at onset; rest tremor as sole initial symptom or sustained dominance of tremor over bradykinesia and rigidity.

- Non-tremor dominant (NTD): Aged 55 years and over at onset; predominantly bradykinetic motor features with no or only mild rest tremor.

- Rapid disease progression without dementia (RDP): death within 10 years from first Parkinson’s disease symptoms, irrespective of age; no dementia, but progression to advanced motor disability by estimated or documented Hoehn & Yahr stage.

The non-tremor dominant category may be split into Akinetic Rigid (AR) and Postural Impairment Gait Disorder (PIGD), but the main difference between the subtypes of PD is whether there are tremors or not, with different brain networks being more affected in the two different types of PD. Moreover, there is a bright side to having tremors, as patients with tremors seem to deteriorate less over time and have less advanced brain pathology [4], and possibly may even have a mild form of PD with tremor called benign tremulous Parkinson [5]. So on the one hand there are people without tremors who nevertheless have Parkinson’s, and whose challenges might be accepting a diagnosis without many visible symptoms, and explaining the diagnosis to others. On the other hand, people who experience tremors as a result of their Parkinson's may have a form of Parkinson’s that is less aggressive and less disabling. The challenge for people with Parkinson's tremors may be whether to – and how long to – hide the tremor (often people tend to sit on their hands or keep their hands in their pockets). Sometimes the mental and emotional effort expended on hiding the tremor is exhausting and eventually takes a toll.

So what are the alternative diagnoses?

- Progressive Nuclear Palsy (PSP) and Multiple System Atrophy (MSA)

If quite early on after experiencing the first symptoms there is loss of balance and walking difficulties, and even falls, then Progressive Nuclear Palsy (PSP) or Multiple System Atrophy (MSA) may be a possibility. In PSP, eye movements are abnormal, and MSA is often accompanied by dizziness when standing due to a drop in blood pressure. There may also be other problems related to the autonomic nervous system, such as urinary difficulties or constipation, to an extent greater than would be expected for typical (idiopathic) Parkinson’s. - Cortical Basal Degeneration (CBD)

There are other rare conditions, such as Cortical Basal Degeneration (CBD) where one arm may feel somewhat disconnected or alien (this phenomenon is actually called “alien limb”) with patients experiencing strange involuntary movements and difficulty handling objects and performing complex tasks - a symptom called apraxia. - Lewy Body Dementia (LBD)

Another clue for the diagnosis not being Parkinson’s is early problems with memory, episodes of confusion, or even hallucinations. Such symptoms may be triggered by medication at much lower doses than would be expected to cause such side effects with “typical” Parkinson’s. This kind of problem raises the suspicion of Lewy Body Dementia (LBD), which in many ways is similar to Parkinson’s, except that the disease progresses more rapidly. Unfortunately, brain scans (such as DAT or FDOPA PET CT) are not good at distinguishing all these conditions, and changes detectable by MRI may appear only later in the course of the disease. - Neuroleptic induced Parkinsonism

Another more common cause of Parkinson’s-like symptoms are your medications, a factor which your physician will also be considering. It is especially important to make sure that you aren’t taking any unnecessary medication that is making your Parkinson’s symptoms worse (or that may even be the sole cause of your symptoms). - Vascular parkinsonism

Parkinson’s-like symptoms may also have been caused by very small strokes which have gone unnoticed. To rule out this option, your physician may want to order a number of tests to look for risk factors that may cause strokes or small vessel disease in the brain. A CT scan or MRI of the brain will help here and may even reveal Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus (NPH). - Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus (NPH)

Normal pressure hydrocephalus is a condition characterized by walking and balance problems, and sometimes also by cognitive impairment and urinary problems. It is diagnosed to a large extent by findings on brain imaging (either CT or MRI). NPH is important to detect since it can respond well to treatment, resolving many troublesome symptoms.

While Parkinson’s is difficult to diagnose, keep in mind that many different conditions may be causing your symptoms. Work closely with your neurologist and family doctor to consider or rule out any condition which may be causing symptoms similar to Parkinson's so that you can receive the most appropriate treatment for your actual condition.

Maybe it isn’t PD?

Well, if it isn’t PD what else might it be? First of all, getting the diagnosis right is the most important step as you will then be much more likely to be treated with the right medications at the right time. You will also be able to educate yourself on what you have and prepare yourself for your future. Of course, nothing is ever 100% certain: the diagnosis may change, or you may get different contradicting opinions. Even if the diagnosis is clear, the prognosis (i.e., the prediction of how the disease will progress in the future) is often more uncertain.

Like all things in life, whether the cup is half full or half empty depends on your mindset.

For example, if you have been diagnosed with a tremulous form of Parkinson’s, a possibility to consider is that you actually have Essential Tremor. Essential Tremor is probably 10 times more common than Parkinson’s and it affects people across a wide range of ages. The older-age onset may overlap with Parkinson’s and even develop into Parkinson’s at some point in the future, but this may take many years, if it happens at all.

If your Parkinson’s is less tremulous, and is perhaps more symmetrical (i.e., affecting both sides of your body equally), or you experience confusion and forgetfulness, or balance problems, or severe constipation and bladder control issues, or marked speech and swallowing difficulties early on, then a different type of “Parkinsonism” should be considered. This is important in order to set expectations appropriately and be cautious with medications and other therapies.

[1] The Lancet [Bloem BR, Okun MS, Klein C. Parkinson's disease. Lancet. 2021 Jun 12;397(10291):2284-2303. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00218-X. Epub 2021 Apr 10. PMID: 33848468.

[2] Armstrong MJ, Okun MS. Time for a New Image of Parkinson Disease. JAMA Neurol. 2020 Nov 1;77(11):1345-1346. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.2412. PMID: 32716484.

[3] Selikhova M, Williams DR, Kempster PA, Holton JL, Revesz T, Lees AJ. A clinico-pathological study of subtypes in Parkinson's disease. Brain. 2009 Nov;132(Pt 11):2947-57. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp234. Epub 2009 Sep 16. PMID: 19759203.

[4] Selikhova M, Kempster P.A, Revesz T, Holton J.L, Lees A.J. Neuropathological findings in benign tremulous Parkinsonism. Mov Disord. 2012;28(2):145-152.

[5] Josephs KA, Matsumoto JY, Ahlskog JE. Benign tremulous parkinsonism. Arch Neurol. 2006 Mar;63(3):354-7. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.3.354. PMID: 16533962.

THIS ARTICLE DOES NOT PROVIDE MEDICAL ADVICE and is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. If you or any other person has a medical concern, you should consult with your health care provider or seek other professional medical treatment immediately. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something that you have read on this website or in any linked article, blog or other materials.